In my last blog post I starting thinking about the concept of lurking in an online community and whether it is a good or bad thing. My instinct tells me that the term is a negative one, that lurking isn’t a good thing since it’s one-sided and no reciprocity exists. So, I did a little reading to develop a position regarding lurking in online communities generally and more specifically in education-related communities. Here’s what I discovered…

Preece et al. (2004) found a number of reasons why people lurk in online communities and that ‘most lurkers are not free-riders’ who take without reciprocating. [While there are numerous definitions of lurkers (Edelman, 2013; Sun et al, 2014) let’s consider them simply as people who have never posted in the online community to which they belong.]

Sun et al (2014) conducted a review of 71 literature sources to come up with a model to explain the motivational factors of online behaviours, in a sense to explain what differentiates lurkers from posters. The authors categorised the factors influencing these behaviours into four as follows:

1. Online community factors including group identity, usability, social norms, pro-sharing and reciprocity (I knew it would turn up somewhere!).

2. Individual factors such as personal characteristics, self-efficacy, goals, desires and needs.

3. Commitment factors are typically affective, normative or continuance.

4. Quality requirement factors are typically non-quantifiable and refer to user expectations of the community that include security, privacy, convenience and reliability.

These factors are certainly useful when seeking to understand online behaviour and to which I will certainly give more consideration going forward.

A Chinese study involving 318 survey respondents by Liao and Chou (2012) on attitudes towards knowledge adoption in online communities found the following hypotheses to be unsupported:

H2: Social trust has a positive influence on the attitude toward knowledge adoption in a virtual community.

H3: The norm of reciprocity has a positive influence on the attitude toward knowledge adoption in a virtual community.

The authors found that increased interactions between members along with shared vision encourages knowledge interaction and adoption. Its findings also supported earlier work by Chow and Chan (2008) that social trust and reciprocity have no influence on attitude. In an educational environment knowledge exchange is an important element and it would be interesting to develop these findings across other cultures.

The distinction between knowledge response and social response is one I hadn’t considered previously and now that I think of it, my peer group’s activity on Discord that I referred to in my last post clearly combines knowledge and social responses. In an interesting study of an online knowledge community, Yan & Jian (2017) found that newcomers to the community who received high quality responses to their questions had a negative influence on their likelihood of providing a future knowledge contribution to the community. On the other hand, social responses (votes, likes etc.) were found to have a strong positive influence on both future knowledge contribution and knowledge seeking.

Relating this to my own practice and certainly my experience of the first semester at Edinburgh, I was slow to get involved in online discussions since it felt that my peers knew more than I did and articulated their thoughts and positions very clearly, often with suitable references. Comparing this with my activity on Twitter, I will often ‘like’ something I agree with but will rarely ‘comment’. Twitter is for me, a place I go to in order to seek knowledge and perhaps this blog is my way of reciprocating, paying forward to readers who may consider undertaking a major educational programme after many years working in industry.

To conclude, I will think of lurking as knowledge seeking in a positive sense. Similarly, I will think of reciprocity in a wider sense than the narrower ‘giver and receiver’ including paying forward.

Until next time,

Sandra

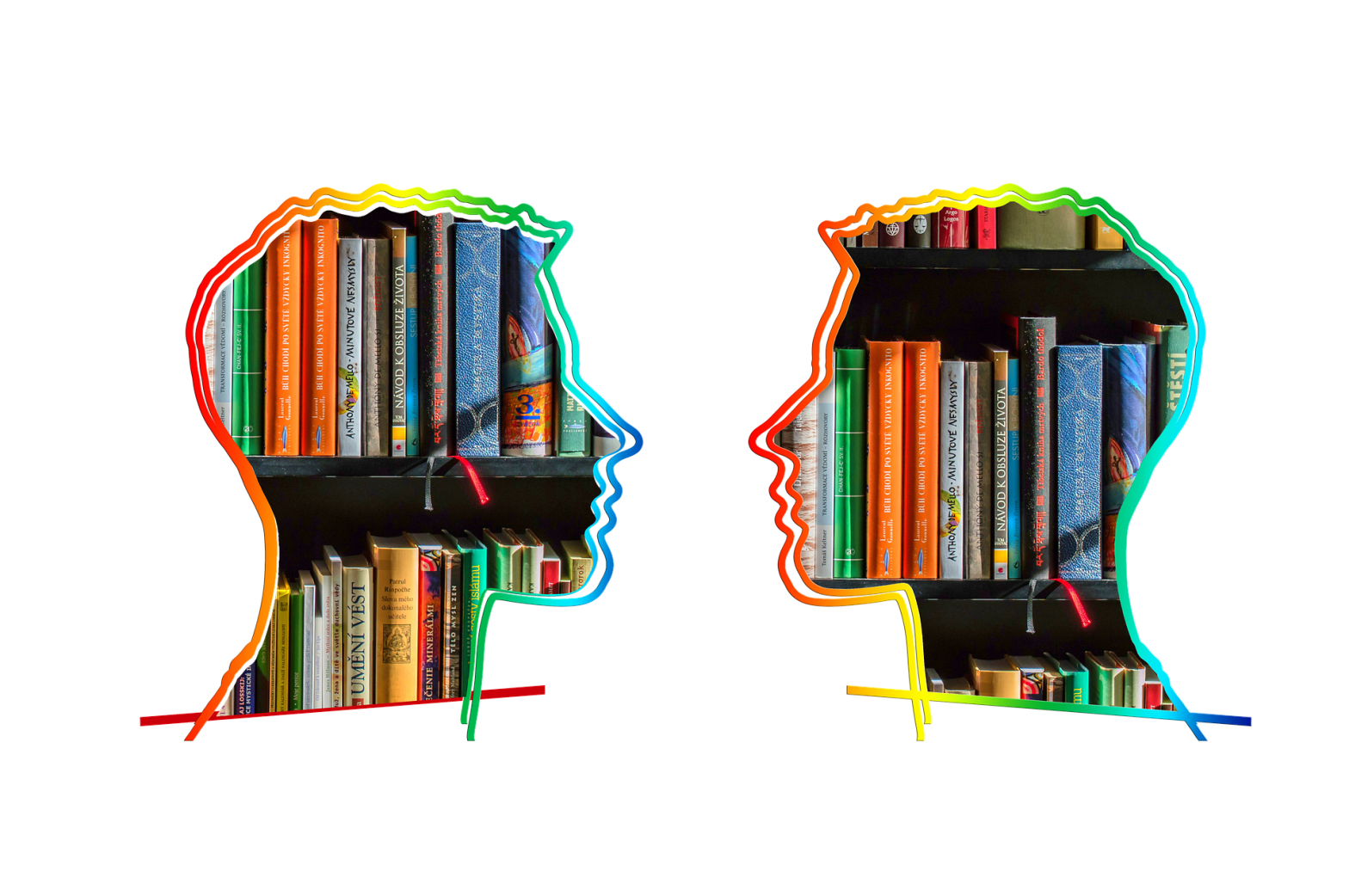

Featured image courtesy of Pixabay

References:

Chow, W.S. and Chan, L.S. (2008), “Social network, social trust and shared goals in organizational knowledge sharing”, Information and Management, Vol. 45 No. 7, pp. 458-65.

Du, Y. (2006). Modeling the Behavior of Lurkers in Online Communities Using Intentional Agents. Computational Intelligence for Modelling, Control and Automation, 2006 and International Conference on Intelligent Agents, Web Technologies and Internet Commerce, International Conference on, p.60.

Edelmann, N. (2013). Reviewing the definitions of ‘‘Lurkers’’ and some implications for online research. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(9), 645–649.

Liao, S. & Chou, E.-Y. (2012). Intention to adopt knowledge through virtual communities: posters vs lurkers. Online Information Review, 36(3), pp.442–461.

Preece, J. (2000). Online Communities: Designing Usability, Supporting Sociability. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 100(9), pp.459–460.

Preece, Nonnecke & Andrews (2004). The top five reasons for lurking: improving community experiences for everyone. Computers in Human Behavior, 20(2), pp.201–223.

Salmon, G. (2001). Online communities: designing usability, supporting sociability: J. Preece, John Wiley, Chichester and New York, 2000, 439 pp, (Book Review). Computers & Education. Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/S0360-1315(01)00031-8

Sun, Rau & Ma (2014). Understanding lurkers in online communities: A literature review. Computers in Human Behavior, 38(C), pp.110–117.

Yan & Jian (2017). Beyond reciprocity: The bystander effect of knowledge response in online knowledge communities. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, pp.9–18.